Best of #econtwitter - Week of August 25, 2024: paper summaries

Welcome readers old and new to this week’s edition of the Best of Econtwitter newsletter. Please submit suggestions — very much including your own work! — over email or on Twitter @just_economics.

Concentration in academic economics

Peeking ahead a few weeks: David Deming has a column this week which has attracted a good amount of discussion:

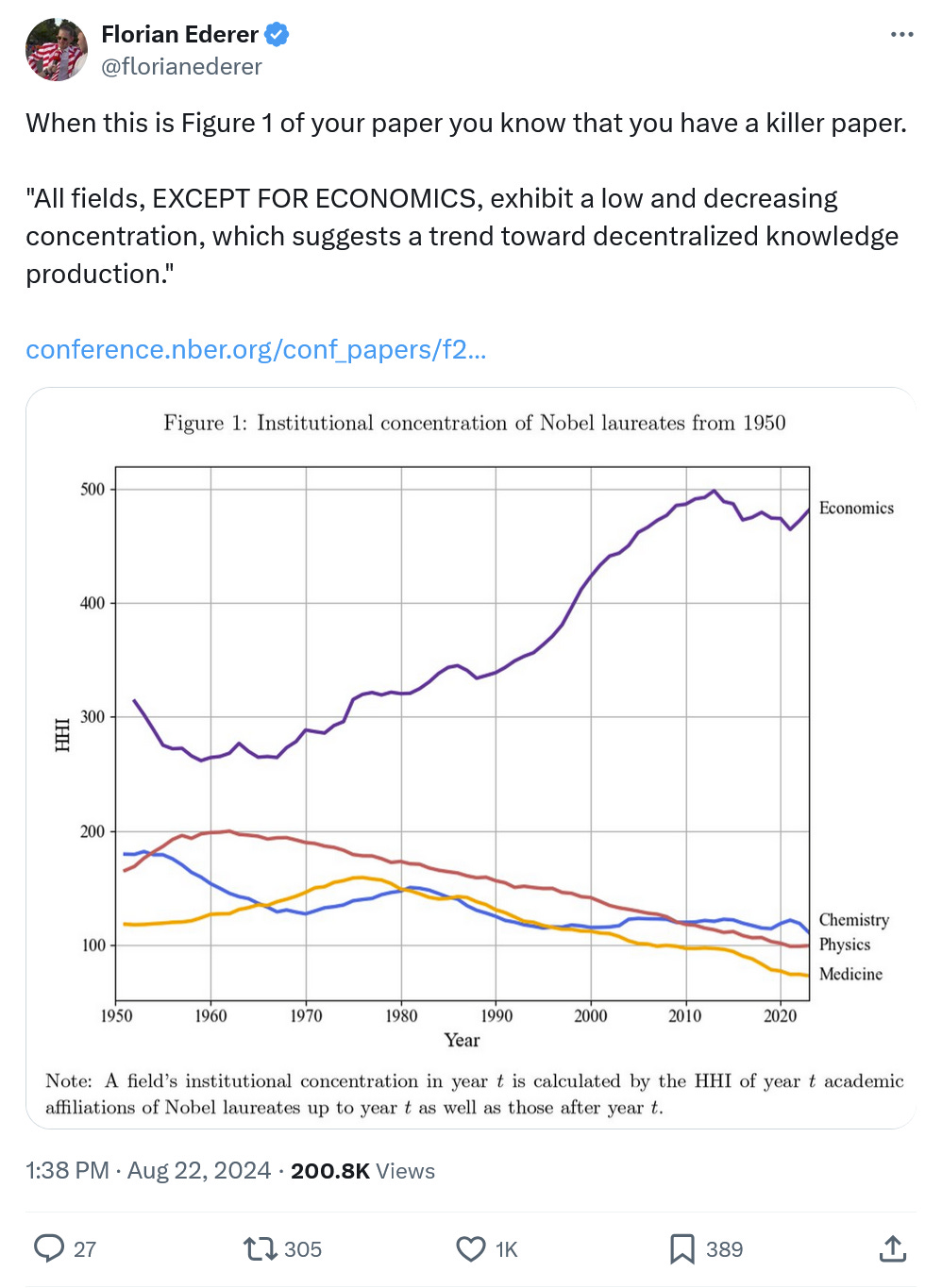

The article is motivated in part by a graph from a paper that went around econtwitter the week of Aug 25 (hence the inclusion of this topic in the newsletter this week):

Here’s an analogy. In traditional markets, it is well-known that you really should not equate concentration with market power; and higher concentration does not automatically imply lower efficiency. Indeed, higher concentration is often a sign of higher efficiency: it is only in very sclerotic markets that the most productive firms are unable to compete away the least productive firms, grow their own market share, and increase concentration.

E.g. Why does southern Europe have so many [unproductive] small businesses (i.e., why does it have such low concentration) — it’s because highly productive entrants cannot grow their market share.

For a review of this, I cannot recommend strongly enough the already-legendary Syverson (2019) JEP. The world is more complicated than the econ 101 Cournot model.

———

Now, here we are observing that institutional concentration in academic economics (under the above metric) is high and rising. A natural inclination is to suppose that this reflects high and rising allocative inefficiency within the profession: “economists best understand the value of a cartel”.

That’s very possible! (And it’s a good joke.) But let’s tell another possible story.

———

Academia is a superstar field, in the Sherwin Rosen sense. Research is also a field with famously high spillovers. Could it be efficient to have the best researchers concentrated in one place?

But why is economics more concentrated than other fields? Is it possible that other fields are simply less efficient — because they are less able to move their best researchers to their best institutions? Well:

Economists move nearly 2x as often as the median field! You can also imagine other testable implications (e.g. when academics move ‘up’ do they become more productive?).

———

In general, when people generate figures showing wide “inequality” within the profession, it is helpful (as always in economics) to close your eyes and imagine: what would the frictionless, perfectly efficient benchmark look like here? Would it also show high inequality?

The purpose of science is to maximize science (in order to maximize overall social welfare). The purpose of science is not to generate egalitarian outcomes for us scientists.

———

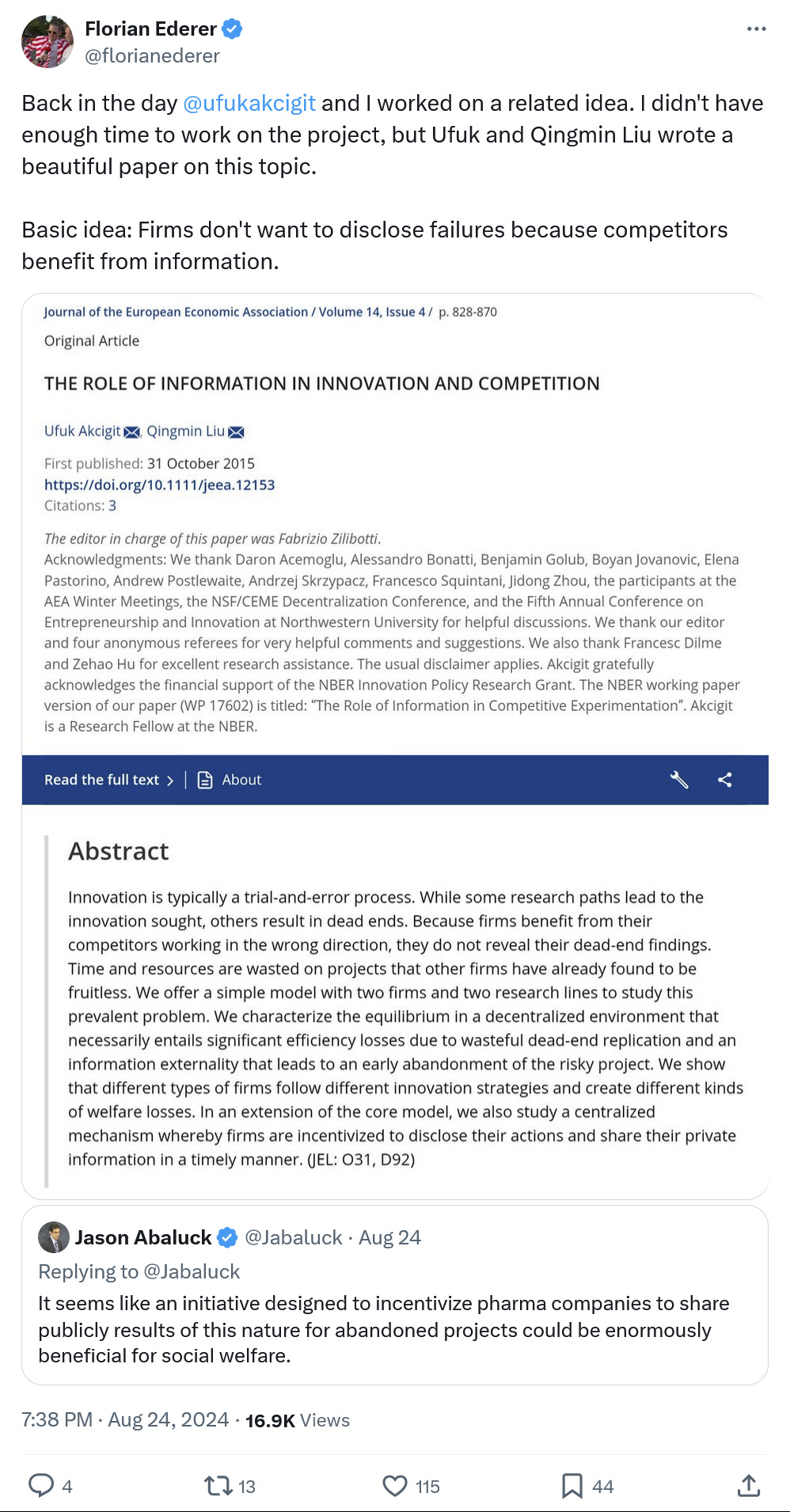

The above is a very small-c conservative defense of the profession. That’s uncomfortable — a theme of the newsletter is that: there is no theorem in economics showing that the market for ideas is efficient (quite the opposite!). It’s SO plausible that the profession is (and academia as a whole is!) just wildly inefficient and broken in really basic ways.

But is high and rising concentration the main problem in economics? Is misallocation of talent across institutions really the big issue? And especially: can you really conclude that from this one figure?

———

I also have a more basic measurement question that I didn’t see answered in the paper. In economics — as shown in the figure above — people move around more than other fields. How does the concentration measure account for this? A given Nobel laureate has more affiliations compared to in other fields. From the paper:

A field’s institutional concentration in year t is calculated by the HHI of year t academic affiliations of Nobel laureates up to year t as well as those after year t

Emphasis added. Given the empirical claims that top economists move around between the top schools (i.e. they do not shuffle at random) and also that good economists move up: am I wrong to ask if high mobility within economics mechanically causes the HHI metric to increase?

When John List gets his Nobel, that will count towards both the University of Central Florida but also towards the University of Chicago. A future Nobel-winning biologist who built her lab at the University of Central Florida and could not move to Chicago (because of the accumulated physical capital of her lab) would only count towards the University of Central Florida. I couldn’t determine from the discussion in sec 2.1-2.2 whether or not this is accurate.

Idiosyncratic favorites

^authors post here, super interesting, though a ~10% increase in time spent on platform seems not trivial

^more meta commentaries please 👍👍

^also see Hartley and Mejia

Institute for Progress papers

3 this week from IFP affiliates, if I’m not mistaken!